In 1945, a farmer in Egypt named Muhammad Ali al-Saman uncovered a glass jar containing 13 leather-bound volumes of papyrus texts dating back to 367 A.D. These texts were likely hidden around the time Saint Athanasius issued Festal letters condemning the use of non-biblical books. Known as the Nag Hammadi Library, or the Chenoboscian Manuscripts or Gnostic Gospels, they had remained buried for over 1,500 years.

The manuscripts were written in Coptic and included complete Gospels of Thomas, Philip, and Mary Magdalene, as well as conversations between Jesus and his disciples. There were also texts from the early Christian era, along with a partial translation of Plato’s Republic. Each codex contains multiple tractates, totaling between 34 and 149 pages. Scholars have examined and validated many of these texts by comparing quotations across early Christian sources and translating between Latin, Greek, and Coptic. Some references date to the second century. Major topics include the resurrection of Jesus, Valentinianism, accounts of Apostle Paul’s journey through various heavenly realms, and the Prayer of Thanksgiving.

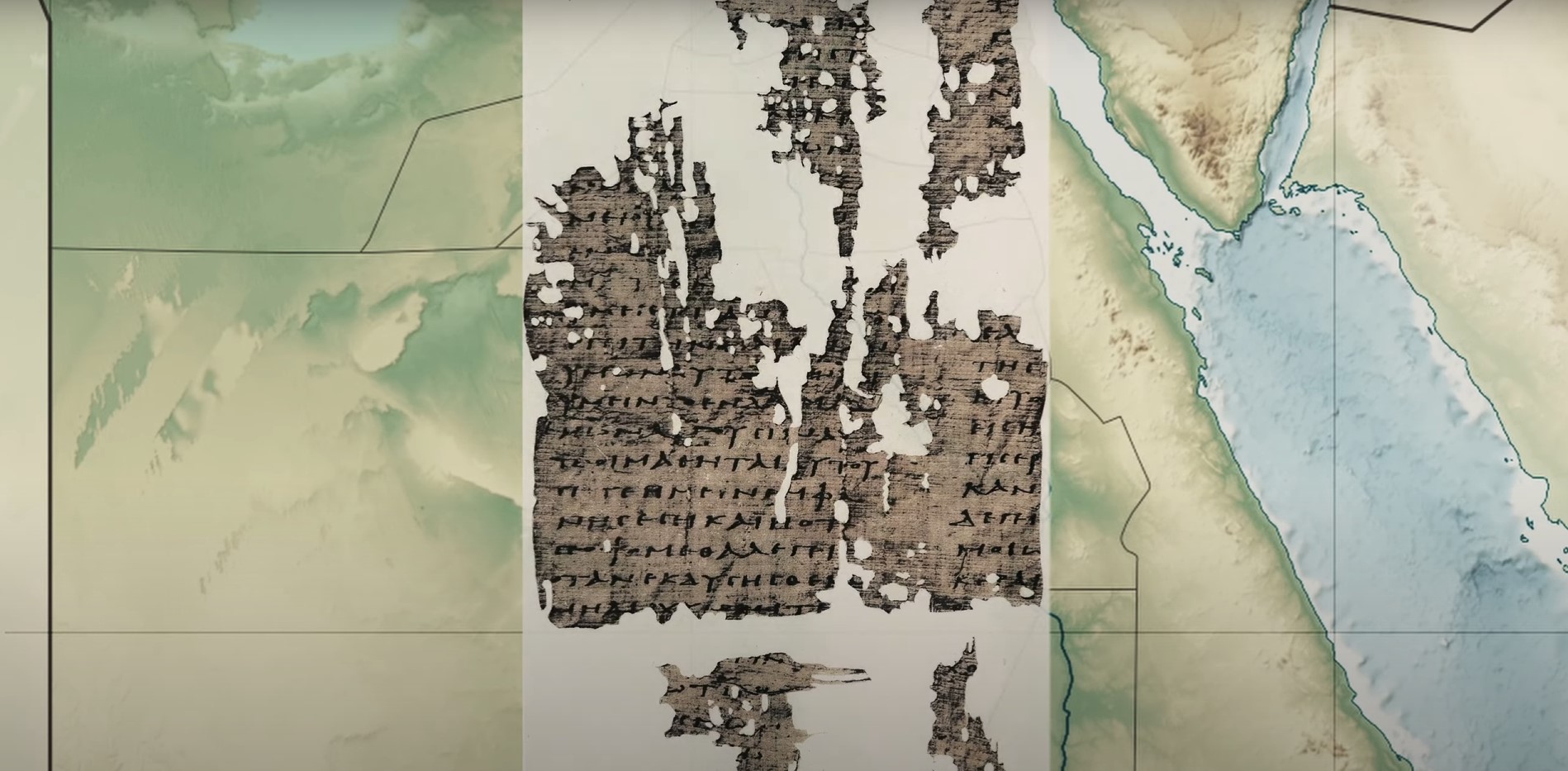

One notable set of texts, Codex 5, holds the First Apocalypse of James, originally in Coptic but later identified in Greek among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri. This vast collection was found in an Egyptian garbage dump in 1898 by Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt. Though the discovery of forbidden texts is not unusual, the scale is significant. Over a century later, only 5,000 pages have been transcribed, with the latest transcription, Volume 86, published in November 2021. The difficulty arises from the poor condition of the documents—some fragments are as small as a single cornflake.

Among the most recognized texts is the Gospel of Thomas, the only complete version dating to the second century. Its phrases attributed to Jesus align with those found in other documents at Oxyrhynchus. One phrase in Thomas states that whoever understands these sayings will not die. Many of the codices emphasize cosmology and Gnosticism. This religious movement emerged in the Mediterranean during the first century within Jewish and Christian groups. Gnostic teachings consider material existence flawed and claim that true salvation is accessible through higher knowledge, or gnosis. A complex system of divine spirits in heavenly realms is central to this belief.

A Christian Gnostic movement arose in the second century, producing texts that claimed apostolic authorship, including works attributed to Peter, Philip, Thomas, and Judas. These writings depicted Jesus as a source of wisdom rather than a messiah. Authorities of the time considered these interpretations problematic, and as a result, many Gnostic texts were hidden for safekeeping.

In the 1970s, researcher James Robinson proposed that the Nag Hammadi codices may have belonged to a Pachomian monastery and were buried following their condemnation. This theory raises questions about early Christian history, prompting debates among scholars about the variety of teachings present in that era.

The Gospel of Mary begins with a statement that all formations and creatures exist together and will return to their own roots. These concepts remain of interest today, appearing in modern works of fiction and analysis. For instance, Philip K. Dick explored Gnosticism in his work VALIS, considering surveillance and god-like forces. Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, inspired by Holy Blood, Holy Grail, drew on Gnostic texts, including those of Philip and Mary Magdalene, to present its own narrative. Although Brown’s story is fictional, it brought renewed attention to Gnostic ideas.

Despite being considered heretical, these texts survive and continue to be translated. Their ongoing study offers insights into early Christian complexity and the range of beliefs that once circulated.

Leave a Reply